George Condo 1992

- julia_mji@me.com

- Aug 25, 2018

- 16 min read

George Condo. © 1989 Marianne Haas.

“Everything enchants him and his incontestible talent seems to be at the service of a fantasy that is a balanced combination of the delicious and the horrible, the abject and the delicate.” — Apollinaire on Picasso, 1912

The same can be said of the mercurial George Condo whose revelatory paintings span the centuries between Madness and Beauty. During the early ’80s, George lived in the East Village. Since then, he’s traveled and exhibited all over the planet, eventually settling in Paris and New York. He has collaborated with William Burroughs, producing four etchings and twelve paintings for Burroughs’s text, Ghost of Chance, published last fall by the Whitney Museum and recently completed his own book, The Big Chief. Besides being the most worldly/other worldly artist I know, he’s also a great natural wit, bon vivant and musician.

Anney Bonney

I have a quote for you: “Personifying is the soul’s answer to egocentricity.”

George Condo

Um … that sounds nice. If the soul and the ego were objects we could look at, the soul would be a translucent heart beating. If you broke away the tissues, you’d destroy a very delicate pulse. And the ego would be an armored unit designed to protect the soul. The soul is in need of protection from people’s inability to restrain from vices, like jealousy, lust, greed … forms of intrusion that the soul and ego try to control. But the need to control brings about more of the same. The ego is a process of elimination that we go through. In order to have this capacity to eliminate, you need the ego to guide the sword. (pause)

AB

Say that again.

GC

Here we are in the ambient soul section room. This is the sound … (George rubs something against the microphone)

AB

You transgress abstraction and figuration, that’s what your personification’s about.

GC

Right.

AB

That’s what it really represents. There’s something of the trickster, Hermes, in you. You’re taking us to the underworld.

GC

Yeah.

AB

The land of plurality.

GC

Mm—hm.

AB

Wilfried Dickhoff beautifully described your work of expanding canvas and alter egos. To me, shadow figures in the world without shadows allude to soulfulness.

GC

Mm—hm. Right.

AB

The darkness, the dogs, the witches you depict.

GC

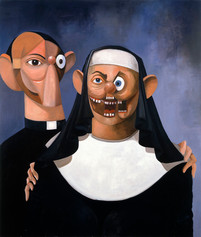

When you add them all up, it’s quite a crew: Indian chiefs, cavemen, office bosses, the nun, two-bit hustlers, low-life criminals, people with one tooth, one eye, protruding chins, enlarged facial features.

AB

The alchemists had a term for that “look”; they called it “vile figura” (or ugly face), and they considered it prima materia, the primal stuff of soul (gold)-making.

GC

But they’re the ordinary, nice people, you know. That’s what my relatives look like. That’s what the early American settlers looked like.

AB

Excuse me, we’ll check your family portraits later.

GC

Listen, if you grow up in New England, you see an old fisherman on the pier very differently from Norman Rockwell, who sees him as a stereotype, which is patronizing and condescending. There’s no sympathetic equality involved. I absolutely feel there’s no intrinsic difference between people. Somebody might say, “George, you’re completely full of shit. Fishermen and bums don’t live in apartments on Madison Avenue or in expensive hotels.” But I say this … “Yes, they do …”

AB

(laughter)

GC

I tend to turn everything into a battle against the world. Eventually, it comes back to the one thing that’s bugging me at the moment. I relate to people like the fisherman and the bum because they can’t get out of their trash pack, no matter what happens. That I can understand. Artists tear themselves apart. Do you know what I mean? I get so far away from the questions you ask me, I don’t even remember what I’m talking about, like the bum walking down the street, screaming at everybody—one minute is just as good as the next.

Portrait Collage Combination, 1990, oil, paper, charcoal and pastel on canvas, 71 × 93 inches.

AB

And one state of mind is just as good as another. So, welcome back to the underworld, land of the free, home of the unconscious … How would you describe your use of psychological foreshortening?

GC

It was an idea of Alfred Brendel’s, describing the way a motif in music could be very minor, but because of the placement in the musical composition, it would affect you first. You may be hit on the street by something totally insignificant that just blows you away for the day, and not even register its importance. And sometimes when I paint, and I walk into a painting expecting to see Vermeer, I get punched in the nose by the old, star-spangled bum with his magic wand, trembling dust, bumming five cents again. These people have a memory bank that they’re working with, a code in life, a little map through the world that they fill. It doesn’t have a lot to do with things like the president of the country or the ruler of a nation. But it does have to do with artists. The Big Chief figured it out …

AB

Who is the “Big Chief”?

GC

The Big Chief is anybody who can take on a number of personalities and fit them all into his heart.

AB

He “bites boundaries” and “expels the insipid affectations of everyday life.”

GC

The affectations I’m dealing with are a miniaturized, diminutive form of politics, more in terms of an 18th-century perspective. Take a Canaletto painting, from where is he sitting? He always seems to be above the Piazza San Marco, in someplace nice, probably just inside one of the buildings you see inside the painting. He manages to catch the street life and shed light on daily politics. He might show two types of characters meeting. But in that particular year, their meeting would convey a peculiar change in the political atmosphere and it would be extremely miniaturized in the painting. My idea is to release this humanizing onto the canvas.

William Burroughs said to me, down in Kansas, “What is painting? You know, that’s probably what you have to write about. What is in the middle of trying to put it into words.” And I said, “That sounds good.” So I brought out The Shattered Line excerpt and read it to him. He perfectly understood that it wasn’t intended to make a broad remark, it was meant to limit itself to a point that is extremely human. Because the affected part of people is the interesting side to me. It’s the real side of them that’s boring. (laughter)

AB

“Real?” Compared to what?

GC

In the minor of ideal reality, every side is equally off-balance. People try to rationalize the center.

AB

Compositionally, I noticed that your earlier portraits focus on a central figure. Of course, there is a major distortion within that figure. That is the irony, that sense of jest and mockery.

GC

There was a time when I realized that the central focal point of portraiture did not have to be representational in any way. You don’t need to paint the body to show the truth about a character. All you need is the head and the hands.

There’s inherent perceptual distortion when you look at a picture, never mind trying to deal with what it is, try to deal with what it’s not. I like what Miles [Davis] said, “Play what’s not there.” That’s why people like Rembrandt’s portraiture. He really painted what was not there. He used paint. That’s what painting is all about, discovering a way to paint because you love paint. I could roll myself in it, drink it, eat it and kill myself, suffocating in it. Some people hate paint and I understand that, too. I can understand people who claw through it, can’t get out of it, can’t put it away.

The Rainbow has a Beard, 1988, oil on canvas, 59 × 47¼ inches.

AB

I have two thoughts. One is that you use baroque ornamentation as an affectational background to offset the “realness” of faces with, say, a green nose, blue flesh, a vertical eyeball, and dogs’ ears. It sweetens the transmutation. Also, I think you’ve been placed in places you’re not, critically speaking that is, such as graffiti and appropriation.

GC

At one time they said, “Condo is a graffiti artist.” Why? Because, at the Basel Art Fair of 1984, Rammelzee, A-1, Crash, and Toxic showed at the Sidney Janis Gallery and I had the box for the Perspective. And they started coming over to my place all the time. I realized that they had checked my work out at Keith’s [Haring]. They came over and they saw my stuff and they were totally into the wild faces. They were like, “Yeah, man, Condo’s in Basel, let’s check him out.” They didn’t copy, you know, they were not into copying. They had already developed their own rigid, perfected styles.

The Appropriation artists said, “Why should we invent something when it’s already there? Let’s just bring it to light.” This last conceptual aspect of discovering it as an overlay, a transparent overlay, was a real breakthrough. It allowed people to relate more than one idea simultaneously without having to be just abstract painters. But I found a way to do this without dealing with appropriation.

AB

And it’s not conceptualization.

GC

No, it’s not. But it’s my way of saying, “This is a painting. It’s not a fake painting, it’s a painting from an imaginary character’s reality.” That’s why I work with a cast of characters, all created carefully. As each of them becomes real, so do their environments, their place of being. Sometimes, I think they even come from some imaginary character’s mind. (laughter)

Oh, I need some water or something. I feel like I have food poisoning tonight.

AB

Should we go to the emergency room?

GC

Yeah, I could get an oxygen tank. No, really, I feel like my stomach is turning inside out. I just had chicken and, uh …

(pause—there’s a search for water)

AB

I like the sense of hysteria, pandemonium, in your pictures.

GC

Mm-hm.

AB

You approach them from a night face.

GC

That’s a nice idea. A god of panic.

AB

Exactly, anxiety and desire.

GC

You can see the Pan pipes of panic screeching off into the night, conjuring up images in smoke, images of the faces you see in the night face, as you call it.

AB

Actually, that’s what Fechner, the founder of Psychophysics, called it.

GC

The anxiety is counter-balancing, is counter-affecting the desire, counter-acting it, deflecting it, hurting it, and making it impossible for it to reach its satisfaction. Once the anxiety is gone, you could give it the old Dalai Lama rap, you know, “Don’t worry, be happy.” Possibly, there’s nothing wrong with that angle, except that it’s easy for him to say, while he’s on the Concorde, flying around the world. Of course, that’s what they say about me, too, you know. (laughter) Help straighten them out. How deep. It’s like acupuncture to me. It’s the difference between acupuncture and driving a stake through your heart. I’m into killing vampires more than healing right now.

AB

The Big Chief mentions healing.

GC

“It’s a self-healing world without the cancers of humanity to destroy it.”

AB

I see the paintings more as metaphors of an ancient text, like healing like, similis similibus curantur. Your willingness to create characters as painful deformities that come from the soul, your willingness to present them center stage, that’s really about taking the cure.

GC

You know what else it’s about? You just made me realize that it’s also about, believe it or not, the Actors’ Studio, Lee Strasberg (via Stanislavski) and his acting method of breaking down. Movies written during that time by people like Tennessee Williams were designed for the main characters to really break down, crack up, totally reveal their rudimentary anxiety, desire, fear, etcetera. Those are the make-it-or-break-it moments in these pictures. In terms of painting, I think of Picasso’s shrieking women with three fingers from the little studies for Guernica. And I think of great performances in the theater.

AB

They share the legacy of mysteries and myth. I was thinking of Dionysus and the origins of Western drama. The tragic flaw. It’s not hubris but fantastic pathology that your paintings expose, over and over again.

GC

Exactly. This is what it is. You know, who is the loser in the story? (laughter)

AB

Guess who—that one-time hero.

GC

Imagine that’s the guy who’s standing there with the elegant fabric behind him on the wall, who looks like he came from Venice, his face is ravaged, and maybe 20 years ago, there was no fabric on the wall, but he was a beautiful person.

The Indian Chief, 1990–91, oil on canvas, 59 × 84¼ inches (three panels).

AB

I think a lot of your imagery comes out of the Puer/Senex complex, the consciousness crisis between young man hero and old man wisdom, e.g., you and William Burroughs, you and Big Chief, you and Picasso, you and you.

Also, you brought up the Guernica women and to me, they are the Bacchantes, frenzied, feral, dismembering their own children. Picasso’s main myth may have been the Minotaur, but even that takes you back to mom consorting with monsters. Your women are wildly disproportionate, with enormous bodies, tiny heads perched on elongated spaghetti necks.

GC

What do you think of all these paintings of women? You know, I’ve done so many of them.

AB

They look like sensuous, intuitive Anima portraits. Call it Soul, Psyche, whatever, that’s how I see them. There’s Hecate, the night goddess who rules over garbage. She’s a dark angel. I see Circe, Demeter, Persephone, Nausicaa and/or their equivalents. Sometimes they’re monsters, the Great Mother, fearsome authority figures …

GC

Monsters are just as beautiful as maidens.

AB

Maybe more so.

GC

The way that, in a Bosch painting, a beetle can have a human head and cellophane-like wings, hairy little flesh-tone legs and spots on his back, with a glowing pink underbelly, exquisite like a jewel. There’s no interest in painting an ordinary pretty woman or pretty-looking man. It’s all about the imagination. I look at women as being art. In my paintings, you never see them enacting against the male world, they’re only in communion with other females.

AB

I glimpsed a few in Paris at your apartment before you sent them to Cologne. One of them actually looked like a chair. I wanted to sit in her.

GC

One was called, The Insulated Woman. She was made entirely out of cotton. (laughter) Another looked like a motorcycle. They had nothing to do with making a statement about “female” … Sometimes, there’s no difference in my paintings between what can happen to a woman, an object, a landscape, or an abstraction. A face could be treated like a very abstract passage in a landscape.

AB

But they’re all brought to life, they’re animated, the root is still anima.

GC

It's not the “masculine anatomy” as form.AB Obviously, but subjects and objects in your paintings have gender just as French nouns do. Figuratively speaking, the ego is masculine and the soul is feminine, the actual forms of your women carry their core qualities like dreams. So, of course, you’re not making a statement about “female,” you’re offering up poetic images that happen to be feminine. It’s not even sexual, it’s beyond that … You are a soul painter.

GC

I don’t want to deal with people, not even women, in any way other than those paintings. If you have … ah … sexual designs on a person, then it’s a question of taking their clothes off, getting them into the studio, putting them on a podium, and painting them from a detached academic point of view. The sexuality revealed is a dishonest one, like Ingres. He creates an idealization of sex. That’s very interesting to Surrealists and Freudians.

AB

But not to Irrealists. It’s about seduction.

GC

Seduction of the viewer by the painting. The sexual aspects of my women paintings … what are those?

AB

That’s a good question, George.

GC

From my point of view, they are used to enhance any sexual qualities that humanity may have left, not to diminish them. I try to make sexuality into something else, maybe it’s not what you’d want, because it can assume any form. And yet, it’s not repelling sexually. For example, the food chain could be an analogous subject. I’ve discussed this with Felix Guattari, he’s a good friend of mine. He deals with incredibly hard-core cases of schizophrenia. He does rip things apart, but not to degrade them.

AB

I think I missed something … What’s the link between sexuality and schizophrenia, besides Salvador Dali?

(There’s talk about George not feeling well, wondering about a 24-hour hot water bottle delivery service and Anney saying she’ll get one for him, if he makes it through the interview). That’s another traditional female aspect—the Nurse.

GC

And another reason I like them. (laughter)

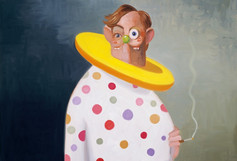

Aqualung, 1991–92, oil on canvas, 81¼ × 199¼ inches (three panels).

AB

The witch paintings to me are about female intelligence/knowledge as dark, powerful and secret. The clowns are about male vulnerability, suffering and foolishness. You are redeeming rejected aspects of sexual archetypes; that’s what people may not want to see, but may need to remember. Memory was the first muse.

Guattari talks about your use of infantile memory. By creating memories that you’re not even sure are memories, you fuse the need to historicize and the need to invent. What if the imaginal is a priori? Imaginary characters pre-exist. It’s not that we make them up, they’re making us up.

GC

Right. Because we don’t exist, we’re not really here now. What’s in the next room isn’t there. There’s no baby, no Anna, no house. You invent it, it’s what you can see in front of your eyes. That’s my interest in Cezanne’s paintings, because it’s as if they’re not really there. He shows you that even by walking around the room and seeing it from a few different points of view, it’s still not there. Picasso supposedly allowed you to see an object from all perspectives, but Cezanne had already done that, by lifting it and placing it again.

AB

I think it’s more about the invisible.

GC

The gravitational force more than what’s being gravitated.

AB

Re-envisioning the relationship between the seen and the unseen. You abstracted that idea in your Shattered Line paintings.

GC

I had done those in my house in Chelmsford, Massachusetts, where I grew up, and that’s a deep, pine forest feeling. It’s got green, it’s got space, it’s got pause, it’s got good punctuation. It’s the oldest town in America, consecrated in 1656. When I brought Anna, my wife, there, she said, “We should just live here. This place you come from is the most beautiful place.” I really wanted to abandon my admiration for European aesthetics and European things. I realized that, ironically, Chelmsford was older than some sections of Paris. I was tired of the pretension some Europeans have about being older and wiser, when, in fact, a lot of them came later, if they came at all. So I was entwined in this happiness of being home, in the States, in Chelmsford, and I had just found this beautiful color of paint down at the hardware store. I was happy not to go to the LeFerre Fauneil where they ground pigment in special recipes for Bonnard, Leger and Vlaminck. I went to a real American paint store and I picked up this charcoal gray latex. I came home, put down the canvas, got out some scotch tape and put it on. I was just about to make this white line all the way down, I made the stroke and suddenly—the gray—when the light went on, the gray became a deep forest and the white became a streak of light that started to move between the pines. And it broke like a shimmering apparition. And then it paused, left a space, a black space and a charcoal gray space, and then it continued again. I looked at it. I went over and took some paper towel to scruffle the edges of each of the white lines. This painting had just become a shattered line, a line that could never be connected again. Barnett Newman could have done it. He did it. A lot of people did it. But there was no truth in it for me until that moment. And that feeling came through for me in two colors, charcoal gray and white. It came through again in a later painting of black and white where both sides of the black flowed into one another, with the white line just broken. That’s the pushing for a cultural progression, human rights; and that had started in the paintings with charcoal gray, which is such an altered state of black in American terminology.

AB

Do you know what Tsim Tsum means?

GC

No.

AB

It’s a mystical Jewish doctrine. Barnett Newman investigated it in a sculptural piece. Basically, the question is: How could God have created the universe if he’s everywhere? Where was there room for the universe? The answer is that God’s ability to withdraw allowed him to create the space for the world. And I think your shattering of the lines contains that truth whereby existential nothingness and the fullness of faith coexist.

GC

That really makes sense. And there’s humor in the idea that, ultimately, all we can do is practice withdrawal and look it over. Like the guy with the third eye and no second one. (laughter)

AB

I get this picture of you and William Burroughs working together in a seance of the unconscious. It starts as a two-character, one-act black comedy and ends as a cast of thousands, an epic that’s accidentally looped.

GC

There was a strange dialogue of unconscious mumbling, a recollection of different characters between us. He would scrape the palette knife and I would say, “Look, there’s the Maharajah, sitting there. You can see the temple crumbling behind him. It was just bombed.”

And he would say, “Look, that building just blew up and turned into a substructure for another operation. Okay, let’s crystallize that unit, and get that one moved out.” So we would scrape out a whole regiment of brush strokes. It was like traveling into Celine’s Journey to the End of the Night, coming from the comic aspect of it, right into the real blood and guts. And it was always a recollection. In just the color application, the way burnt umber and white tones over a brick-orange build up to a flesh that recalls Goya or Joshua Reynolds. Cracks between some leaves become that red undertone of canvas. It can come from anywhere at all, from Hell, or a rusty old Maple leaf.

Seated Figure with Towel, 1989, oil on canvas, 95 × 80 inches.

AB

Your new combinations deal with separation and collaboration differently, in an eccentric formality.

GC

Like an artist’s reaction to a soup can sparking off a work of art, a lot of these paintings were obvious responses to being in my studio, seeing my paintings stacked against one another. Their stylistic interrogations conflicted and contrasted, but together they made a whole.

AB

That’s an inversion of your earlier expanding canvas strategy.

GC

It is.

AB

At first glance, these combinations seem harmless and familiar, but then they sneak up behind you and implode. They dare you to accept the unity of multiple dimensions.

GC

I think so, because the human mind now has the task of watching a TV show with commercials in the middle of it. What if you’re seeing a news broadcast, they just bombed the White House and in the middle of that you have little Miss Daisy doing her dishes …

This is the ideal psychological foreshortening we talked about earlier. This is not Cubism and walking around the canvas. This is Psychological Cubism.

AB

… which may produce unwanted awareness in the age of information addiction.

GC

I think that, in the future, people will be able to see like that, their minds are already being conditioned—for example, if the eye were a wheel calibrated like a clock, between twelve and one, and there were so many seconds and that area was unrelated to eight and nine; that’s the way the eye is perceiving the combinations. It’s a lot to take in, it’s a capsulization of a lifetime in each piece, but it’s a way for me to open a painting up, like Rembrandt’s anatomy lesson.

In order for the depth of psychological experience to take place, everything has to be like a dentist’s chair—you sit down and they’re nice and they put the gas on … then they just rip your mouth off. (laughter) Rip your teeth out.

AB

Well, thank you, Dr. Condo. Where’s the nitrous?

GC

It’s hanging over your head in the safety compartment.

Anney Bonney is a painter who lives and works in New York.

George Condo's interview by Anney Bonney at BOMB magazine published on July 1st, 1992

Comments